|

|

Is "The Constitution in Exile" A Myth?:

In a book review in the latest issue of The New Republic,

Cass Sunstein renews his claims that "[t]here is increasing talk [among

conservatives] of what is being called the Constitution in Exile — the

Constitution of 1932, Herbert Hoover's Constitution before Roosevelt's

New Deal." Sunstein has suggested this a number of times before (see,

e.g., here and here), and the claim has been repeated recently by The New York Times and by my colleague Jeffrey Rosen.

The suggestion is that influential conservative lawyers express their

goal for the courts as being the restoration of "the Constitution in

Exile." The odd thing is, I can't recall ever

hearing a conservative use the phrase "the Constitution in Exile." I

asked a couple of prominent conservatives if they had ever heard the

phrase, and they had the same reaction: they had never heard the phrase

used by anyone except Cass Sunstein and those discussing Sunstein's

claims. As best I can tell, the phrase "Constitution in Exile" originally appeared in a book review by D.C. Circuit Judge Douglas H. Ginsburg in 1995 in the course of discussing the nondelegation doctrine in the journal Regulation.

As you can see from the article itself, the use of the phrase is not

exactly prominent: it appears once, near the end of the introduction.

In any event, the use of the phrase in Ginsburg's review inspired lots

of critical commentary from legal academics, including its own

symposium in the Duke Law Journal (you can read the Foreward to the symposium issue here).

But my initial google and Westlaw research failed to uncover direct

evidence — beyond the initial book review, which I just read today —

that conservatives or libertarians have used this phrase to describe

their goals. Why does it matter, you wonder? After

all, some on the right do want the Supreme Court to bolster some

constitutional doctrines that the Court deeemphasized in the post-New

Deal era. Critics could decide that they think this agenda should be

described as amounting to a wish to restore the Constitution in Exile.

But if I understand it correctly, Sunstein's claim is different: the

claim is that conservatives themselves use the phrase —

"right-wing activists . . . talk about restoration of the 'Constitution

in Exile'." The difference matters, I think, because describing

something as being "in exile" suggests recognition of a revolutionary

agenda. If a government is overthrown and the old leaders flee but

remain intact, referring to the old leaders as "the government in

exile" suggests that the old government is just biding its time before

it can launch a counterrevolution. The rhetorical power of Sunstein's

claim lies in its suggestion that conservatives see their own goals as

truly revolutionary. If the phrase is not actually used by

conservatives, but rather is a characterization by their critics, I

think that makes a notable difference. I have

enabled comments. I am particularly interested in uses of the phrase

"Constitution in Exile" by conservatives that I may have missed. (This

isn't my specialty area, so it's quite possible that it is in fact used

and I just missed it.) Also, if the comment function isn't working, try leaving a comment here. UPDATE: Steve Bainbridge offers commentary here.

Cass Sunstein Responds to "Constitution in Exile" Post:

Last week I wrote a post " Is the 'Constitution in Exile' A Myth?,"

questioning claims that an influential block of conservatives have an

agenda for the courts that they themselves describe as restoring the

"Constitution in Exile." I noted that I could only find one use of the

phrase "Constitution in Exile" by a conservative — a single comment

buried in a 1995 book review by Judge Douglas Ginsburg. I asked whether

the phrase "Constitution in Exile" was something that conservatives

actually used, or rather was merely a phrase that critics (most notably

Cass Sunstein) have used to describe what they contend is a growing

conservative legal movement. Cass Sunstein e-mailed me a response, which he has graciously agreed to let me post: As you say, the phrase comes from Chief Judge Ginsburg of the DC Circuit, in a piece in Regulation

magazine. Without using the phrase, he also spells out his argument in

some detail in a remarkable piece on constitutionalism in the Supreme

Court Economic Review, from the Cato Institute. This piece has been

given as a lecture at several places, including the University of

Chicago Law School, where a packed room gave it respectful attention.

A

glimpse of the argument: Judge Ginsburg writes that judges were

faithful to the Constitution for most of the nation's history - from

the founding, in fact, through the first third of the twentieth

century. But sometime in the 1930s, "the wheels began to come off." His

strongest complaint is about the Supreme Court's decision, in 1937, to

uphold the National Labor Relations Act. Judge Ginsburg objects that

this is "loose reasoning" and "a stark break from the Court's

precedent." In his view, the Court's acceptance of the National Labor

Relations Act is not merely "extreme"; it is also "illustrative."

Randy

Barnett's powerful book, Restoring the Lost Constitution, is definitely

in the same general vein (consider the title!); so too is some of the

work of my colleague Richard Epstein, especially but not only on the

commerce power. So too for much conservative writing on the

nondelegation doctrine. Justice Thomas writes significant opinions that

support the general goal (restoring the lost constitution, or what

Judge Ginsburg calls the Constitution in Exile), as of course you know;

and Scalia is often with him.

The idea of the lost

Constitution, or the Constitution in Exile, or the original

constitution, is very prominent in the conservative community. In fact

the idea of originalism goes hand-in-hand, for many people, with the

idea of a Constitution in Exile, whether or not that phrase is used. I

think the Constitution in Exile phrase is especially evocative, and I

admire Judge Ginsburg a great deal (despite major disagreements on this

point). But the goal is what's important, not the specific term, and it

seems to me that we've all witnessed the rise of that goal, especially

in the last decade or so, with the increasing assertion of a certain

form of originalism. I have two responses, one

narrow and the other broader. The narrow point is that I understand

Sunstein to agree with my first post that there is no evidence that a

conservative has used the phrase "Constitution in Exile" outside of a

single reference in a 1995 book review. On this point, my apologies to

Professor Sunstein if I simply misread his prior writings; I had

understood Sunstein to be claiming that conservatives are themselves

using the phrase "the Constitution in Exile" to describe their legal

goals. To the extent that we are in agreement that the term is

primarily Sunstein's, and has not been used by conservatives outside of

a 1995 book review — and even then, apparently only as a descriptive

matter, not as a normative one — then that addresses the topic of my

prior post. This is an important point of consensus, I think: we can

all agree that there is no evidence that conservatives refer to their

agenda for the courts as restoring a Constitution in Exile. Now,

let's turn to the broader question, one that I did not address in my

first post: terminology aside, is there a conservative movement to

restore a pre-New Deal constitution? Unfortunately, I am not the best

person to answer this: I am not a constitutional theorist, don't really

follow the literature, and don't teach constitutional law. Nor do I

know how you measure when a certain amount of writing or scholarship

amounts to a "movement." If there is a conservative movement to restore

a constitution in exile, however, it is news to me. I can think of a

handful of conservative law professors who have some pretty far-out

views about how to reshape constitutional law, but I tend to think that

this says more about constitutional theory in legal academia today than

it does about any "movement" in conservative legal circles. Nor do I

see how their claims amount to wanting wholesale restoration of the

pre-New Deal constitution. Perhaps part of the problem is that I don't

see the direct connection between originalism and restoring a

constitution in exile. I see the former as a mode of constitutional

interpretation, and one that leaves open a reconciliation with stare

decisis. The latter apparently would dismiss stare decisis and attempt

to reconstruct a very particular constitutional order. Some

readers will agree with Sunstein that there is in fact a conservative

constitution-in-exile movement. But if you take this position, don't

you have to agree that there is a liberal constitution-in-exile

movement, too? Here's a thought experiment to show you what I mean.

Let's imagine Cass Sunstein has a cousin who is identical to Sunstein

in every way except one: he is a conservative. This conservative

version of Sunstein - let's call him Moonstein - could write something

like this: There is increasing talk among

liberals of what is being called "the Constitution in Exile" — the

Constitution of the 1960s, Justice Brennan's Constitution. Their target

is Ronald Reagan and the Bushes, who they claim pushed a false

Constitutional vision designed to strip the Bill of Rights of its

essential guarantees and emphasize property rights over human rights.

They have set as their goal the restoration of the progressive

Constitution forced into exile by by a string of Republican

presidencies starting in 1968.

The organizing strategy

behind the liberal Constitution in Exile movement was explained by

Professor Mark Graber in a 2002 law review article, Rethinking Equal

Protection in Dark Times, 4 U. Pa. J. Const. L. 314 (2002). Graber

urged his fellow liberals to plot for the return of the progressive

"constitution in exile." He wrote: "Progressive arguments . . . are

best understood as constructing shadow constitutions or

constitutions-in-exile. Parties out of power in many nations form

shadow cabinets. These bodies consist of the persons who might hold

various executive offices when that coalition gains control of the

government. The American equivalent apparently is the shadow

constitution. Scholars out of power in the United States author various

shadow constitutions that detail the constitutional meanings that might

become the fundamental law of the land should the author's preferred

coalition gain control of the federal government."

Restoring

the liberal Constutitution in Exile has become an increasingly dominant

theme of progressive legal thinkers. For example, a collection of some

of the nation's most prominent progressive legal minds (including Cass

Sunstein) will be meeting at Yale Law School in the spring to develop

"a shared vision of what, at least broadly speaking, that Constitution

in Exile is, so that we can support and work for its realization." A website and blog

set up for the conference reveals the agenda. For example, Bruce

Ackerman sets as one of the more modest items on the agenda to "[r]oot

out the federalism decisions since Lopez, and return to the status quo,

circa 1994. Root all of them out, not some of them." His more

"transformative" agenda would include "overrul[ing the] Slaughterhouse

[cases] and mak[ing] the [Privileges and Immunities] Clause the basis

for fundamental positive rights of citizenship." Other scholars at the

conference urge a new Constitution entirely. One scholar urges that the

Constitution must be reconceived to serve "a basic purpose: the

protection of human dignity." Another contends that the law must

"revisit both the 14/19th amendments and the general welfare clauses so

as to take on the deep inequalities of the contemporary social order

inside the United States, to reconceive the meaning of equality." A

fair response to Moonstein might note that Moonstein is cherry-picking

a few comments and imagining that these professors have real influence

in order to create the impression of a major movement afoot. The fact

that a few law professors are arguing in favor of major constitutional

change shouldn't be terribly surprising: that's what constitutional law

professors do, right? My sense is that the same criticism applies to

Sunstein and claims of a conservative constitution-in-exile movement. I have enabled comments. Please, civil and respectful comments only.

"Constitution in Exile" in NYT:

Tomorrow's New York Times magazine will feature a Jeff Rosen article on alleged conservative movement to restore the "Constitution in Exile." Slate has a preview here.

A prediction: The article will conflate efforts to restore textual

limits on enumerated powers with "Lochnerism" and judicial enforcement

of libertarian ideology. Rumor also has it at least one co-conspirator

will be featured in the piece.

Rosen on the "Constitution in Exile":

I’m sure the legal blogosphere will be abuzz with discussions of Jeff Rosen’s N.Y. Times magazine piece on the purported "Constitution in Exile" movement.

Jeff was a Yale Law classmate of mine, and I'm generally a great

admirer of his work. But I do want to take issue with a couple of

things in this particular piece.

First, I take issue with the whole idea that there is a "Constitution in Exile movement," as such. [UPDATE: co-blogger Orin makes similar points here.] "Constitution in Exile" is a phrase used by Judge Douglas Ginsburg in an obscure article in Regulation

magazine in 1995. From then until 2001, I, as someone who knows

probably just about every libertarian and most Federalist Society law

professors in the United States (there aren't that many of us), and who

teaches on the most libertarian law faculty in the nation, never heard

the phrase. Instead, the phrase was pretty much ignored until 2001,

when it was picked up and publicized by liberals. In October 2001, the Duke Law Journal,

at the behest of some liberal law professors assumedly worried about

what would happen to constitutional law under Bush appointees,

published a symposium on the Constitution in Exile. Thereafter, other

left-wingers, such as Doug Kendall of the Community Rights Council and

Professor Cass Sunstein, began to write about some dark conspiracy

among right-wingers to restore something called "the Constitution in

Exile."

Yet, outside of Ginsburg’s article, I still have not seen or heard

any conservative or libertarian use the phrase, except to deny that

they ever use it. And a quick Westlaw search shows that no conservative

or libertarian constitutional scholar has ever used it in a law review

article. I acknowledge that some Federalist types, including me, do

believe that various pre-New Deal constitutional doctrines should be

revived. But let's be clear on the fact that the idea that there is

some organized "Constitution in Exile movement," that is in fact using

that phrase is pure fiction. Why does this matter? Because the phrase

"Constitution in Exile movement" implies that there is some organized

group that has a specific platform. In fact, what you really have is a

very loose-knit group of libertarian-oriented intellectuals with many

disagreements among themselves. Would I, for example, be considered a

member of the "Constitution in Exile movement" even though I don't buy

Epstein's theory of the Takings Clause, and think Lochner was

probably wrongly decided? [UPDATE: It also matters because there's a

reason actual believers wouldn't use the "Constituion in Exile"

moniker. Unlike conservative orginialists, the more libertarian

elements on the legal right--the folks that Rosen interviews for his

piece--generally don't have any nostalgia for the pre-New Deal or even

pre-Warren Court jurisprudence on issues such as the Equal Protection

Clause's protection of minorities, the Incorporation of the Bill of

Rights against the states, the First Amendment, etc.; I know that both

Barnett and Epstein, for example, think Griswold was correctly decided,

and probably think Roe, or at least Casey, was too. The

phrase "Constitution in Exile" suggests a desire to revive pre-New Deal

constitutionalism whole hog, when the folks Rosen refers too mostly

want to add additional limits on government power. In fact, the

interest groups most critical to the Dems on judicial

nominations--feminists, ACLU, minority activists--would almost

certainly by happier with a Justice Janice Brown or Alex Kozinski than

with a Justice Luttig or Bork].

[material deleted; it was unfair]

Finally, Jeff, while not explicitly critical of libertarian

constitutional theory, does seem to be implicitly raising the alarm

regarding potential future conservative or libertarian judicial

activism. I hope it's not impolite to mention that this alarm-raising

comes with a touch of irony from someone whose first published law

review work defended the proposition that the Ninth Amendment protects

judicially enforceable natural rights, and, moreover, that courts

should refuse to enforce a constitutional amendment banning

flag-burning, because such an amendment would itself be an

unconstituitonal invasion of natural rights. 100 Yale Law Journal 1073 (1991).

UPDATE: Oh, and it should go without saying that none of the

individuals Rosen identifies as pushing the purported "Constitution in

Exile movement"--Greve, Epstein, Barnett, Bolick, etc.--have any

political power. The odds that Bush will nominate a libertarian type to

the Supreme Court (unless its Janice Brown for other reasons) are slim

to none. He may nominate someone like Luttig who believes in some

limitations on federal power, but you would be hard pressed to find any

originalist who believes that the current scope of federal power

complies with the original meaning of the Constitution. Even Bork, who

certainly has little in common with Greve et al., has always

acknowledged this point, though he's argued that it's too late to do

anything about it, a rather odd (and politically convenient)

perspective for an originalist, and one that's always been

controversial even among his acolytes. And if the Bush people were

really intent on pushing a constitutional revolution, wouldn't they

have followed in Reagan's footsteps and appointed a prodigious fraction

of conservative and libertarian legal academics to the federal bench?

Correcting Rosen's History:

Jeff

Rosen is a learned guy who has written some rather perceptive things

about the so-called Lochner era in his law review scholarhip. See 66

Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1241. Unfortunately, in his journalistic piece in the Times magazine, he simply regurgitates Progressive myths when recounting constitutional history. To wit:

Rosen: All restoration fantasies have a golden age, a lost world

that is based, at least to a degree, in historical fact. For the

Constitution in Exile movement, that world is the era of Republican

dominance in the United States from 1896 through the Roaring Twenties.

O.K., besides the fact that there is no "Constitution in Exile movement", there

is nothing blatantly inaccurate about the above; the Republicans did

dominate the United States from 1896 to the Roaring Twenties. But Jeff

is clearly implying that there was some correlation between libertarian

interpretation of the Constitution and Republican politics, in a way

that would both draw parallels to today, but also suggest that such

views have always been tied up in partisanship. In fact, however, some

of the most libertarian Justices of the period Jeff refers to–Melville

Fuller (Cleveland), Rufus Peckham (Cleveland), and James McReynolds

(Wilson) were appointed by Democrats. Some of the most statist

Justices–Holmes (Roosevelt), Stone (Coolidge), Roberts (Hoover), and,

at the tail end, Cardozo (Hoover) were appointed by Republicans.

Constitutional interpretation simply wasn’t a partisan (though it was a

political) issue, and with few exceptions the Justices of the period

from both parties accepted constitutional limitations on both federal

and state regulatory power that none of today's Justices would

countenance.

Rosen: Even as the Progressive movement gathered steam, seeking

to protect workers from what it saw as the ravages of an unregulated

market, American courts during that period steadfastly preserved an

ideal of free enterprise, routinely striking down laws that were said

to restrict economic competition.

There is a wealth of scholarship, starting with historian Charles Warren in the 1910s and 20s, through recent work by myself and others (and Cushman, 83 Va. L. Rev. 559;

Melvin I. Urofsky, State Courts and Protective Legislation During the

Progressive Era: A Reevaluation, 72 J. Am. Hist. 63 (1985)), showing

that the Supreme Court, especially through 1923, rarely invalidated

economic regulations. The Court, and lower courts, allowed restrictions

on free enterprise ranging from bans on options trading to Sabbath laws

to child labor laws (at the state level) to a wide range of draconian

professional licensing laws to many, many more types of regulations.

Between 1923 to 1934, the Supreme Court grew somewhat more aggressive

about invalidating regulatory laws, but, at the same time, (1) state

courts virtually abdicated the field; and (2) even the Supreme Court

upheld some rather unprecedented and draconian regulations, such as the

Railway Labor Act (unanimous opinion at 281 U.S. 548).

Rosen: The most famous constitutional battle of the time was the 1905 Supreme Court case Lochner v. New York,

which challenged a law that was passed by the New York State

Legislature, establishing a maximum number of working hours for bakers.

In a dissenting opinion, Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. objected

that "The Fourteenth Amendment does not enact Mr. Herbert Spencer's

Social Statics," referring to the celebrated Social Darwinist and

advocate of laissez-faire economics.

Spencer has been unfairly tarred as a "Social Darwinist", and Holmes

himself is far more accurately depicted as a Social Darwinist, but I

won’t go into that here. I will say that first, Social Statics

is a book by Spencer, something that for some reason most

constitutional scholars don’t know. The book advocated the libertarian

"law of equal freedom," which Holmes analogized to the sic utere tuo ut alienum non laedes

principle in law (use your property in such a way so that it does not

hurt that of others). Holmes pointed out that the sic utere principle

had never been adopted by the Court as part of the U.S. Constitution

(and indeed, the Court, Holmes noted, upheld many types of economic

regulation), so he could not understand why maximum hours laws would be

unconstitutional. Note that Holmes was neither accusing his brethren of

being Social Darwinists, or of adopting a laissez-faire view of the

Constitution; indeed, on the latter point, he was pointing out that Lochner

was inconsistent the with the Court's general indifference or hostility

to laissez-faire as a constitutional principle. By stating that the

Fourteenth Amendment did not enact Social Statics, Holmes was

simply stating that the Fourteenth Amendment did not require the states

to adopt a radical libertarian system of government.* (Relatedly,

Spencer was not simply an advocate of laissez-faire in the economic

realm, but a radical libertarian more generally, who, among other

things, was an early and passionate supporter of women's rights.)

Rosen: Even after the election of Roosevelt in 1932, the Supreme

Court continued to invoke laissez-faire economics to strike down

federal laws, including signature New Deal legislation like the

National Industrial Recovery Act.

You can read the NIRA case here,

and I challenge you to find any hint of laissez-faire economics in the

opinion. Indeed, the unconstitutionality of the fascistic NIRA was not

even controversial on the Court–all nine Justices, including Brandeis,

Cardozo, Stone, and Roberts, thought the law clearly exceeded federal

power. More generally, Jeff should know better than to mix and match

the Lochner line of due process cases and the scope of federal power

cases. The two lines of cases happened to both be overturned around the

same time during the New Deal, but they were in fact, separate lines of

cases, with separate rationales, and "inconsistent" results (e.g., the

Supreme Court upheld state child labor laws challenged under the due

process clause, but invalidated federal child labor laws as beyond the

scope of federal power).

I recognize that the history Jeff recounts is not the main point of

his article. However, if one is going to write about those who want to

restore pre-New Deal doctrines, it's important to know, as libertarian

academics who support full or partial "restoration" generally do, what

those doctrines actually were and what effect they had. Relying on

Progressive mythology in critiquing the views of libertarians who know

better simply isn't helpful.

* Clarification: Enforcing liberty of contract in one case hardly

means that the Court was adopting an overall laissez faire view of the

Constitution. Holmes was arguing that Lochner was a logical opinion

only if the Court was willing to apply sic utere broadly as a matter of

constitutional law. This is actually quite silly if you read the

majority opinion, which draws quite reasonable distinctions between

constitutional workplace regulatory laws meant to protect worker or

public health, and unconstitutional restrictions on liberty of contract

that have no valid "police power" purpose. Holmes was a master of the

flip aphorism, but one shouldn't confuse flip aphorisms with legal

acumen.

The Constitution-in-Exile Myth Returns:

I just finished reading the New York Times

piece by my friend and colleague Jeffrey Rosen on the alleged

"Constitution in Exile" movement. Having written on this topic a few

months ago, see here and here, and also having discussed it a bit with Rosen during his research into the piece, I wanted to add a couple of thoughts. In

my view, the problem with Rosen's essay is that it tries to portray the

decades-old writings of a small number of scholars and activists as an

existing and influential "movement." I don't think the evidence adds

up. The handful of scholars and activists that are supposed to make up

this alleged movement are pretty far removed from the set of players in

the Bush Administration that are actually setting policy and selecting

judges these days. Maybe the Reagan Justice Department was enthralled

with the writings of Richard Epstein; the Bush 43 Justice Department

isn't. Rosen downplays this problem, but I think a

close look at the evidence reveals that Rosen is stretching. For

example, here is what Rosen says about the influence of the alleged

C-I-E movement in the current administration: The

influence of the Constitution in Exile movement . . is not always

clear, since the concerns of the White House often overlap with

concerns of conservatives broadly sympathetic to business interests or

the concerns of more traditional federalists. ''If you mentioned the

phrase 'Constitution in Exile' in White House meetings I was in, no one

would know what the hell you were talking about,'' a former White House

official, who spoke on condition of anonymity because of the

sensitivity of the topic, told me. ''But a lot of people believe in the

principles of the movement without knowing the phrase. And the nominees

will reflect that.'' According to the former official, during Bush's

first term, David S. Addington, the vice president's counsel, would

often press the Justice Department to object that proposed laws and

regulations exceeded the limits of Congress's power. ''People like

Addington hate the federal government, hate Congress,'' the former

official said. ''They're in a deregulatory mood,'' he added, and they

believe that ''the second term is the time to really do this stuff.'' So

the best we can do is get the view of one anonymous person that other

mostly unnamed people believe in a set of principles that the anonymous

person says match the views of this alleged movement? Surely the last

four years of Bush 43 would have provided more concrete evidence than

that. As for Addington, note what Rosen does not: that while Addington

in the Vice President's office urged DOJ to take a position that may or

may not have reflected the influence of the alleged movement, DOJ

apparently refused all of these urgings. So much for influence. Rosen

also overplays his hand in describing the development of the alleged

movement. Consider his description of Douglas Ginsburg's 1995 essay

that apparently contains the only known use of the phrase "Constitution

In Exile" by a conservative or libertarian. Rosen portrays the essay as

a manifesto urging an eager audience to take action: By

1995, the Constitution in Exile movement had reached what appeared to

be a turning point. The Republicans had recently taken over both houses

of Congress after pledging, in their Contract With America, to rein in

the federal government. And the Supreme Court, by rediscovering limits

on Congress's power in Lopez, seemed to be answering the call. For

conservative advocacy groups and public-interest law firms, the

possibilities for litigation looked encouraging.

In a

reflection of the new mood, Douglas Ginsburg wrote an article in

Regulation, a libertarian magazine published by the Cato Institute,

calling for the resurrection of ''the Constitution in Exile.'' He noted

that for 60 years, proper constitutional limits on government power had

been abandoned. ''The memory of these ancient exiles, banished for

standing in opposition to unlimited government,'' he wrote with a hint

of wistful grandiosity, ''is kept alive by a few scholars who labor on

in the hope of a restoration, a second coming of the Constitution of

liberty — even if perhaps not in their own lifetimes.'' If you go back and read the actual article,

though, a different picture emerges. Ginsburg's alleged manifesto was a

review of a book by David Schoenbrod arguing for the return of a strong

nondelegation doctrine in constitutional law. The bit about the

Constitutution in Exile is a two-sentence paragraph at the end of

Ginsburg's introduction, before he turns to Schoenbrod. Ginsburg

doesn't applaud Schoenbrod's Constitution-in-Exile-ish proposal,

however; he is quite critical of it. Ginsburg's review argues that the

answer to the policy concerns raised by excessive delegation is not

constitutional law, but statutory law: he embraces an idea introduced

by Justice Stephen Breyer in a 1984 article in the Georgetown Law Journal

that expensive regulations should require affirmative Congressional

approval. While Rosen says Ginsburg called for a resurrection of the

Constitution in Exile, Ginsburg actually recommended Congressional

adoption of a proposal made by that right-wing radical Stephen Breyer. I have enabled comments. As always, civil and on-point comments only.

The NY Times and the Hunt For the "Constitution in Exile":

Given that the Constitution in Exile movement doesn't seem to exist, some may be wondering why the editors at the New York Times commissioned Jeff Rosen to write a long and detailed cover story about it for the Sunday Times magazine. I've been mulling it over, and have come up with four possible explanations for their interest: 1)

Any old newspaper can report on a real trend, but it takes the paper of

record to invent one. Feeling emboldened by their successful invention

of "man dates" last week, the editors wanted a greater challenge.

2)

The Times editors have been reading lots of Hayek recently and have

become fascinated with libertarian thought. Their library stopped

subscribing to Regulation back in 1996, however, so they didn't know about more recent developments.

3) Any story that features a hot picture of Richard Epstein is going to sell a lot of newspapers. 'Nuff said.

4)

Tainting future Bush judicial picks with some kind of shadowy extremism

might just influence a future Senate vote. All the better if the

shadowy movement doesn't actually exist: the harder it is to find the

movement, the harder it is to prove that Bush's pick has no connection

to it. I'm sure other possibilities exist, but these four seem the most plausible to me.

Accurate But Fake:

Over the past few weeks, I have had two interesting experiences with the fact checking process of the MSM: the New Yorker and the New York Times to be precise. The New Yorker

was the first to contact me to fact check Margaret Talbot's story on

Justice Scalia. In order to show that the Justice was exaggerating the

history of originalism, the original story contained some questionable

claims. I found it interesting, and reassuring, that the fact checkers

sought out a professor like me who subscribes to originalism to double

check these claims. All the errors I noted were corrected in the final

story, though of course this did not unduly affect its overall negative

slant. A week later, I was having dinner in Princeton with a group of

professors and graduate students after my talk there. When I asked if

anyone had seen the article, Keith Whittington (author of

Constitutional Interpretation: Textual Meaning, Original Intent, and Judicial Review)

piped up that he had been contacted to fact check it. So not one but

TWO originalist scholars had been contacted. Very impressive indeed.

Last week, I was contacted by the NYT to fact check what was going to

be said about me in Jeff Rosen's Sunday Magazine story on the so-called

"Constitution in Exile" movement. Like others, I had never heard this

phrase until long after it was being used by "moderates" like Cass

Sunstein. As the blogosphere is already effectively dismembering the

substance of Rosen's in-depth report on the VLC (Vast Libertarian

Conspiracy), I thought I would confine myself to my experience with the

Times fact checking process.

Almost all the claims the fact checker wanted to confirm had some sort

of minor defect, most of which had nothing to do with the obviously

negative slant of the piece. For example, it described Angel Raich as

formerly paralyzed; it had the wrong number of states adopting medical

cannabis statutes.

One erroneous claim, however, was definitely part of the story's slant

that I was a part of an organized "Constitution In Exile" movement:

that the Cato Institute had either paid for or published my book, Restoring the Lost Constitution.

This claim was removed from the finished article after I explained that

the book had been published by Princeton in its normal acquisition

process, but that Cato had assisted me during my university sabbatical

year when I wrote the first draft of the manuscript (as I acknowledge

in the book). Score one for the fact checking process.

The only accurate but misleading claim that remained was that my "book

identifies a series of regulations that he says the courts should

consider constitutionally suspect, from environmental laws to laws

forbidding the mere possession of ordinary firearms, therapeutic drugs

or pornography."

I knew about the environmental law issue, of course, as I mentioned it

to Jeff and offered it in the book as an example of an "unhappy ending"

that I think represents an oversight in the original Constitution. Jeff

had tried very hard to get me to say what laws would be

unconstitutional under my approach. As my approach is presumptive,

however, this is hard to answer in the abstract, as the success of any

challenge to a particular law will depend a lot on specifics. An

analysis of the constitutionality of any particular law would require a

lengthy analysis.

So I pointed to the section of my book where I discuss what I think is

the unfortunate consequence that some environmental activities would be

within the jurisdiction of state not federal regulation. In the book, I

offer this as one of the very rare instances in which the Founders did

not anticipate a genuine cross-border national problem properly handled

at the national level. He ended up using this in his story, of course,

as I knew he would—albeit without my disclaimer that I offered this as

an example of a bad consequence I would like to see corrected by

constitutional amendment (that would pass in a week if the Court ever

held Congress to its Commerce Clause power on this issue).

I had to ask the fact checker for the pages where I discuss "firearms,

therapeutic drugs, and pornography" as I did not recall having done so.

Sure enough all three examples are in one single sentence as

illustrations of the sort of pure "possessory" laws that would be

suspect under the conception of the state police power that I defend in

the book. When I read the fact checker the entire paragraph (he did not

have the whole sentence or a copy of the book), I stressed that it

applied only to pure "possessory" crimes. I told him that, contrary to

what the use of these examples implied, I never claimed that the

manufacture or sale of these items could not, constitutionally, be

regulated. He said that he would consult with the editors and get back

to me. Over dinner, it occurred to me that if they added "mere"

possession, this would ameliorate (though not entirely eliminate) the

implication that my approach ruled out all regulation. After dinner,

the phone rang and the fact checker informed me that the editors had

decided to insert the word "mere" in front of possession (without my

even suggesting they do so).

What is interesting about having experienced this fact checking process

first hand is that, in both cases, there was a sincere effort by the

fact checkers to verify suspect claims--claims that really were

inaccurate. In each case, where I explained my objections, these claims

were then corrected. Yet the overall misleading slant of the NYT story

was preserved. None of this is the fact checker's fault, or even the

fault of the fact checking process, which I found to be admirable. With

both the New Yorker

and NYT, the fact checkers were sincere in their desire to get the

facts correct. Both were very impressive and the resulting articles

were more accurate as a result.

But an important lesson here is that accurate facts can still be used

to compile a highly distorted story like the one by Jeff Rosen, a

person I have known and respected for many years—dating back to his

very useful student article on the founders' conception of unenumerated

rights. It was out of this respect for Jeff that I gave him a long and

candid phone interview last February, but I could tell from the

questions what the slant would ultimately be.

Despite the MSM's claim to greater accuracy than blogs, fact checkers cannot alter the spin an author can put on what the National Lampoon

used to call "true facts"—especially when this is the very spin the

editors had in mind when they solicited the article. Apart from the

inaccurate constitutional history noted by David, I cannot quarrel with

any of the facts reported in Jeff's piece. They are true, even if the

impression given by the story to credulous readers of the New York

Times is false. Fittingly, the "accurate but fake" nature of the

"Constitution in Exile" story is best illustrated—literally—by the

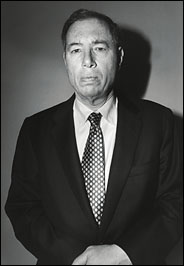

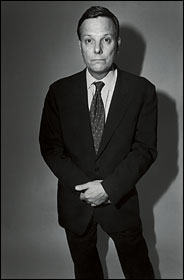

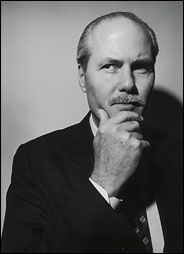

unrecognizable morgue photos of Richard Epstein and Michael Greve—both

would be completely unrecognizable to me had I not read who they were

supposed to be—and the "Snidely Whiplash" picture of Chip Mellor.

While all were certainly actual photos taken of these three men by the

Times photographer, at the same time they all were fake. How fitting.

Rosen Channeling Schwartz:

Back in March 1987, Prof. Herman Schwartz wrote an article for The Nation that bears striking resemblance to Rosen's N.Y. Times

piece (to be clear, I'm not accusing Rosen of plagiarism, or even of

ever having read Schwartz's article; it's just that 1987 seems like a

time of similar hysteria over perceived libertarian influence on

conservative judicial thought prompted, as in 1987, by a forthcoming

vacancy on the Court, and by the nomination of a libertarian (Bernard

Siegan instead of Janice Brown) to a Court of Appeals seat. Of course,

Siegan got voted down, and the next USSC nominee was the very

unlibertarian Robert Bork):

A new breed of theorists is calling for vigorous judicial activism

in defense of--what else?--property rights. Concurrently, the pre-New

Deal Supreme Court, which struck down federal and state laws against

union busting, child labor and other abusive business practices, is

back in favor. . . . This neo neoconservatism has been most thoroughly

developed by University of Chicago Law professor Richard Epstein, one

of the administration's most influential legal advisers. . . Epstein

argues that those clauses of the Constitution that forbid the

government to take over private property except for public use and wit

fair compensation, and that bar the states from excessive interference

with contracts, where intended to ensure that private property remained

virtually sacrosanct. He then reads those clauses as rendering

unconstitutional most welfare, environmental, is stating gift tax,

renewal, zoning and then control laws, along with almost every other

piece of social legislation of the past two centuries. Unlike most

constitutional lawyers, he thinks the Court decided correctly in Lochner v. New York,

when, in the name of property and contract rights, it struck down an

attempt to limit working hours for bakers. . . . Such judicial activism

is usually condemned in the administration circles. . . . Nevertheless,

this new faith in an activist judiciary is gaining ground among some on

the right who are normally its harshest critics.

Schwartz's concerns about a libertarian takeover of the federal

judiciary were, alas, seriously premature, as are, undoubtedly,

Rosen's. In fact, though libertarians are a growing (though still

miniscule) presence in legal academia, their political influence has

probably decreased where it counts. Republican honchos are more

concerned than ever about their religious conservative base, and the

relevant folks in the Justice Department--who in the Reagan years were

a highly intellectual group that took ideas, including libertarian

ideas very seriously--are undoubtedly very bright, committed

conservative lawyers, but show, as far as I can tell, few signs of

similar intellectual ferment (in practicalterms, e.g., other than

McConnell, where are the Borks, Winters, Easterbrooks, Ginsburgs,

Williamses, and Posners on the judicial nomination radar screen?)

Randy Barnett Wins Spooner Award:

No, not for supposed spoonerisms,

which he isn't prone to, and which are named for a different Spooner.

Laissez Faire Books awarded him their 2004 Lysander Spooner Award for

Advancing the Literature of Liberty, for his Restoring the Lost Constitution. Congratulations to Randy!

Laissez Faire Books' blog also has a post on Randy and that New York Times Magazine article.

Constitution-in-Exile Debate:

Over at Legal Affairs,

the Debate Club will be featuring a debate this week between Cass

Sunstein and co-blogger Randy Barnett about the alleged

Constitution-in-Exile movement. Only Cass has written so far, and his

initial post strikes me as, well, odd. His post is very vague, but if

I'm not mistaken he is suggesting that many or most judicial

conservatives believe in some kind of radical vision of the

Constitution in Exile. The key question seems to be which radical

vision different conservatives like: as best I can tell, Sunstein is

suggesting that some like Ginsburgian strike-everything-down radical

activism, while others like Scalian uphold-everything radical activism.

Huh? Well, I guess we'll have to wait and see how the debate shakes

out. Of course I'll be particularly interested to see what my

co-blogger Randy has to say. (Hat tip: Howard) UPDATE: Randy posted his initial reply to Sunstein just I was posting. An excerpt: Let

me begin this week-long exchange, Cass, with a denial. There is no

"Constitution in Exile" movement, either literally or figuratively. As

for literally, I and others had not even heard the expression, plucked

from an obscure book review by Judge Douglas Ginsburg, until well after

folks like you and Jeff Rosen had started using it to describe their

intellectual opponents. And as author of the 2004 book, Restoring the

Lost Constitution: The Presumption of Liberty, I would seem to be at

the heart of whatever movement supposedly exists.

For

obscure reasons that we may perhaps glean from this week's debate, the

phrase "Constitution in Exile" viscerally appeals to critics of

scholars and judges who, like me, favor interpreting the Constitution

as amended according to its original meaning. Maybe it makes these

"originalists" sound kooky or marginal or radical—like Russian nobility

with their shadow governments futilely planning their return to power

from the irrelevant comfort of London tea rooms. Maybe this rhetorical

move has something to do with undermining future nominees to the

Supreme Court who may be originalists. Sounds like it will be an interesting week over at Debate Club.

More on the "Constitution in Exile":

In a previous post

on the purported (but non-existent) "Constitution in Exile movement," I

suggested that liberals who use the phrase are likely trying to imply

not simply that some elite legal libertarians would like to revive

constitutional limitations on government power that were enforced

before the New Deal, but also that these scholars were hostile to all

constitutional law jurisprudence that developed since the New Deal. But

I noted:

Unlike conservative originalists, the more libertarian elements on

the legal right--the folks that Rosen interviews for his

piece--generally don't have any nostalgia for the pre-New Deal or even

pre-Warren Court jurisprudence on issues such as the Equal Protection

Clause's protection of minorities, the Incorporation of the Bill of

Rights against the states, the First Amendment, etc.; I know that both

Barnett and Epstein, for example, think Griswold was correctly decided, and probably think Roe, or at least Casey, was too [update: Will Baude points out that Epstein has been critical of Roe and seems skeptical of Casey].

Now, Cass Sunstein writes:

Would the Constitution of 1787, or of 1920,* increase our liberty or

diminish it? For now, let's just notice the real radicalism of any

effort to go in that direction. In 1787 and in 1920, racial segregation

by the federal and state governments was believed to be constitutional.

In 1787 and 1920, sex discrimination by government was just fine. In

1787 and 1920, there was no general right of privacy. In 1920, free

speech was understood quite narrowly. Congress would almost certainly

have been forbidden to protect workers' right to strike. In 1920,

minimum wage laws were unconstitutional.

But as co-blogger Randy points out in a response to Sunstein, there

doesn't seem to be anyone out there, liberal, conservative, or

libertarian, who thinks that the pre-New Deal Supreme Court had things

completely right, or even almost right. Conservative originalists

object to the entire line of Lochner cases, including Meyer, Adkins, and Gitlow

(see below). Libertarians (and many conservatives) think the Court had

too narrow an interpretation of freedom of speech, and tunnel vision on

issues of race.

But perhaps Judge Doug Ginsburg, originator of the "Constitution in

Exile" phrase, is an exception, and he, and perhaps a secret group of

acolytes, want to restore constitutional law to its state in 1930?

Sunstein writes:

For Judge Ginsburg, and for some others, the court had the

Constitution right in 1930. Judge Ginsburg also believes that the

Constitution in Exile forbids Congress from "delegating" its authority

to administrative agencies, such as the Environmental Protection

Agency, by giving them broad discretion. Judge Ginsburg believes that

since 1930, the Supreme Court has "blinked away" individual rights,

above all the right to private property—and created rights of its own

choosing, like the right to choose abortion.

But here is the sum total of what Judge Ginsburg has to say about the "Constitution in Exile":

So for 60 years the nondelegation doctrine has existed only as part

of the Constitution-in-exile, along with the doctrines of enumerated

powers, unconstitutional conditions, and substantive due process, and

their textual cousins, the Necessary and Proper, Contracts, Takings,

and Commerce Clauses. The memory of these ancient exiles, banished for

standing in opposition to unlimited government, is kept alive by a few

scholars who labor on in the hope of a restoration, a second coming of

the Constitution of liberty-even if perhaps not in their own lifetimes.

I find it difficult to tease out of this paragraph--much less out of

Ginsburg's subsequent repudiation of the nondelegation doctine in the

same piece--what Sunstein does.

*Sunstein uses 1920 advisedly, because by 1930--still pre-New Deal days, let's keep in mind--the Court had dealt a blow to sex discrimination in Adkins v. Children's Hospital (later reversed by a New Deal Court decision), and Meyer v. Nebraska

in 1923 had recognized broad liberty rights under the Due Process

Clause, likely including a version of the right to privacy, but New

Deal decisions had cabined such rights dramatically until Griswold v. Connecticut in

1965. So, if anything, in at least some ways the pre-New Deal Court was

far more agreeable to Sunstein on "liberty" issues than was the New

Deal Court. (And the Court's broader free speech jurisprudence began

with Gitlow in 1925.)

Debate With Sunstein--Part Deux:

My reply to Cass Sunstein's latest post on the "Constitution in Exile" is now up in the Legal Affairs Debate Club.

Sunstein-Barnett Debate, Episode III:

My reply to Cass Sunstein's latest post on the "Constitution in Exile" is now up at LegalAffairs' Debate Club. For another take on the so-called Constitution-in-Exile movement, check out Michael Greve's essay Liberals in Exile.

A Revisionist View of Bolling v. Sharpe:

In yesterday's installment of the Sunstein/Barnett debate, Sunstein raised the case of Bolling v. Sharpe, holding that the federal government may not segregate schools in the District of Columbia. Randy responded:

You are right to point out that the Supreme Court's decision in Bolling v. Sharpe

is very difficult to reconcile with the text of the Constitution. For

this reason, you know that among constitutional scholars of all stripes

Bolling is one of the most controversial and difficult cases

ever decided by the Court. I do not have a fully worked-out opinion on

this complex issue, but suppose that a commitment to originalism

entails the reversal of Bolling.

I have an article forthcoming on Bolling in the Georgetown Law Journal,

in which I explain that Bolling has been incorrectly interpreted as a

"reverse incorporation" case applying 14th Amendment equal protection

standards to the Federal government under the Fifth Amendment, when it

was really a pure Lochnerian due process case, a fact Warren ultimately

chose to obscure in the final opinion. I conclude:

[W]ith its roots in Buchanan v. Warley and the 1920s

educational liberty cases, the liberty right to be from from compelled

segregation in education is perhaps better-grounded than the [currenly

recognized] liberty right to terminate one’s pregnancy, to engage in

homosexual sodomy, or to be free from arbitrary punitive damages

awards. This will not satisfy critics who oppose the Court’s

substantive due process jurisprudence across the board. But for the

vast majority of legal scholars who do support the Court’s current

substantive due process jurisprudence, Bolling should be an easy case to defend.

Sunstein-Barnett Debate, Round 4:

My response to Cass Sunstein's latest foray on the so-called "Constitution in Exile" is up now on the LegalAffairs Debate Club. Only one more round to go.

Sunstein-Barnett Debate, Grand Finale!

In his last post of our week-long debate on the supposed "Constitution

in Exile" movement, Cass Sunstein goes out with a bang. My final reply

is now posted here.

Three Lessons for the Great Debate About to Begin:

I recall very well the debates over the nominations of Robert Bork and

Clarence Thomas to the Supreme Court. Both featured the most elevated

public discourse over constitutional interpretation in my lifetime. Of

course, both nominations were also marred by ugly personal attacks and

false charges. For the upcoming nomination, we can expect both types of

discourse. To that end, some may wish to review the debate I recently

had with Cass Sunstein over at LegalAffairs.org.

Cass and others such as Jeff Rosen have promoted the trope

"Constitution in Exile" to describe those who favor enforcing the whole

Constitution according to its original meaning. The alternative is to

enforce only portions of the text according to whatever meaning yields

"good" results.

It is useful to review this debate to see the difference in our

approaches so one can better track and participate constructively in

the forthcoming debate. My approach focuses on restoring portions of

the "lost" Constitution that the Courts have long ignored--such as the

Commerce Clause, the Necessary and Proper Clause, the Second Amendment,

the "public use" portion of the Takings Clause, the Ninth Amendment,

and the Privileges or Immunities Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment.

Cass consistently focused, not on the text of the Constitution, but on

a list of results--either good results he favored preserving or bad

results he contended that the fictitious "Constitution in Exile

movement" wanted to achieve.

LESSON ONE: Watch the switch from a list of ignored textual provision to good and bad results.

This debate should not allowed to be turned into a debate over results.

It should instead be a debate over constitutional method and the

restoration of portions of the text that have long been discarded. This

includes challenges to judicial conservatives who, like Justice Scalia,

would continue to ignore the Ninth Amendment or Privileges or

Immunities Clause because they fail to meet his standard for a "rule of

law." Ignoring portions of the Constitution because they fail to

conform to your theory of the "rule of law" is no different than

ignoring portions that fail to conform to your theory of "justice."

LESSON TWO: Watch the switch from meaningful scrutiny to extremely

deferential "rational basis" scrutiny, as a means of continuing to

ignore portions of the text.

And by "ignoring" I include adopting an extremely deferential "rational

basis" approach that yields all discretion to the legislative branches,

as Justice Stevens explicitly and Justice Scalia implicitly recently

did in the medical cannabis case when applying the Necessary and Proper

Clause. This is a game that both "liberals" and "conservatives" can

play. It is not "activist" for judges to demand of legislatures that

they have a real and justified reason for restricting the liberties of

the people--something more than mere assertion. Whenever legislatures

need not meet any burden of justification whatsoever--e.g. Justice

Stevens' approach in both Raich and Kelo--the scheme of federalism and limited enumerated powers is undermined.

LESSON THREE: Watch for an appeal to "precedent" to attack a nominee

who may favor reviving the original meaning of portions of the

text--e.g. the "public use" portion of the Takings Clause--that have

been ignored for far too long.

Another technique for ignoring the text is to elevate the importance of

past nonoriginalist judicial decisions in the name of "precedent." The

"liberal" side of the Court has never accepted the "precedents" of Lopez and Morrison.

Nor could "liberal" or "moderate" justice be counted on to accept any

precedent that does not accord with the results that drive their

approaches. For the same reason, a "conservative" (or libertarian)

Justice should give little weight to nonoriginalist precedent that

justifies ignoring portions of the text. It is the Constitution to

which a judge (and Senator) takes an oath, not past decisions by the

Supreme Court. The issue of precedent is very complicated, however. I

explain some of these complications here.

On the other hand, you may expect nominees to deflect potential

criticisms by embracing precedent to avoid the charge that they would

revive now ignored portions of the text. Given that many originalists

do favor adhering to precedent, this defense may be entirely sincere.

To the extent, however, that a nominees is willing to elevate the past

opinions of the Court over the text of the Constitution where the two

clearly conflict, he or she would be abandoning anything like an

originalist approach to interpretation. This would not be a good sign

for the future. Inevitably selective reliance on precedent is one of

the most common methods of avoiding the text of the Constitution when

the text is an obstacle to achieving particular results--my definition

of "judicial activism."

Let me offer as my hope for this forthcoming debate, the penultimate paragraph of my exchange with Cass:

Over the course of this week, Legal Affairs readers have

been provided a preview of a great debate that lies ahead. As my final

contribution to our discussion, let me express my hopes and aspirations

for that debate. I hope that the political process upon which we rely

to select Supreme Court Justices will not be thwarted by name calling,

conspiracy mongering, or false claims about bad motives on either side.

I hope that judicial nominees will not be presented with a laundry list

of results intended to serve as a litmus test for ideological

acceptability. I hope they will be asked instead about their judicial

philosophy and their commitment to the rule of law. I hope that those

who participate in this great debate will frame their arguments in

language that clarifies the issues rather than obscures them. And I

most fervently hope that the debate will not be conducted in a

topsy-turvy newspeak that charges originalists with being

insufficiently conservative and equates adhering to the rule of law

supplied by the Constitution of the United States with activism or

radicalism! You can read the entire debate here.

Justice Thomas On Precedent:

In my earlier post I offer this as Lesson Three for watching the upcoming Supreme Court confirmation hearings:

LESSON THREE: Watch for an appeal to "precedent" to

attack a nominee who may favor reviving the original meaning of

portions of the text--e.g. the "public use" portion of the Takings

Clause--that have been ignored for far too long. On Pejmanesque, Pejman Yousefzadeh, observes:

One of the reasons why I like Justice Thomas is that while

he respects precedent, he is willing to cast it off if the original

precedential decision did not conform with original intent. And why

shouldn't he? There is no point in compounding a mistake, after all. He then links to his interesting Tech Central column, Needed: Thomist Jurisprudence. Here is a taste of that:

Those who -- like me -- are disheartened by the decisions

in Raich and Kelo may potentially take heart in the hope that Justice

Thomas's powerful dissents will have sown the seeds for the emergence

of a Court majority in the future that will reflect Justice Thomas's

thinking. Perhaps that new majority will be crafted via help from

Justice O'Connor's successor -- who could do worse than to adopt

Justice Thomas's approach to the law and to intellectual issues. As law

professor Orin Kerr puts it, "The next time someone insists that

conservatives like Justice Thomas will do anything to defend corporate

interests against the powerless -- and particularly against powerless

racial minorities -- feel free to point them to Justice Thomas's

eloquent dissenting opinion in Kelo. So much for that idea." Let me take this as an opportunity to make two points:

First, Justice Thomas is a conservative politically, not a libertarian.

I am completely certain of this because I have personally heard him say

so very recently and with gusto. Nevertheless, while there are Thomas

opinions with which I disagree (e.g. his dissent in Lawrence v. Texas),

his philosophy of judging comes closest to the one I recommend, which

shows how method should come before results. Where I disagree with him,

it is incumbent upon me to show how he has deviated from original

meaning (as I think he sometimes has done). I still find it interesting

that Justice Scalia did not join Justice Thomas in his concurring

originalist opinions in Lopez and Morrison, or Justice Thomas's originalist dissenting opinion in Kelo. In Kelo,

Justice Scalia (along with Justice Thomas) joined Justice O'Connor's

excellent, but nonoriginalist, dissent instead. I believe this tells us

much about the different judicial philosophies of these two

conservative justices.

Second, it is worth considering Justice Thomas's own words about precedent from his Kelo dissent:

The Court relies almost exclusively on this Court’s prior

cases to derive today’s far-reaching, and dangerous, result. But the

principles this Court should employ to dispose of this case are found

in the Public Use Clause itself, not in Justice Peckham’s high opinion

of reclamation laws. When faced with a clash of constitutional

principle and a line of unreasoned cases wholly divorced from the text,

history, and structure of our founding document, we should not hesitate

to resolve the tension in favor of the Constitution’s original meaning.

This is the judicial philosophy that I hope will be shared

by whoever the President decides to nominate. Otherwise, "judicial

conservatives" will forever be taking their orders from nonoriginalist

justices of the past, rather than from the text of the Constitution to

which they take their oaths, and which most of the people still think

should restrict those who govern them.

Article on Bolling v. Sharpe:

SSRN has posted my article, "Bolling, Equal Protection, Due Process, and Lochnerphobia," forthcoming in the Georgetown Law Journal. Here is the abstract:

In Brown v. Board of Education, the United States Supreme

Court invalidated state and local school segregation laws as a

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment's Equal Protection Clause. That

same day, in Bolling v. Sharpe, the Court held unconstitutional

de jure segregation in Washington, D.C.'s public schools under the

Fifth Amendment's Due Process Clause. Fifty years after it was decided,

Bolling remains one of the Warren Court's most controversial decisions.

The controversy reflects the widespread belief that the outcome in Bolling reflected the Justices' political preferences and was not a sound interpretation of the Due Process Clause. The Bolling

Court stands accused of inventing the idea that due process includes a

guarantee of equal protection equivalent to that of the Fourteenth

Amendment's Equal Protection Clause.

A careful analysis of Bolling v. Sharpe, however, reveals some surprises. First, the almost universal portrayal of Bolling

as an opinion relying on an equal protection component of the Fifth

Amendment's Due Process Clause is incorrect. In fact, Bolling was a

substantive due process opinion with roots in Lochner era cases such as

Buchanan v. Warley, Meyer v. Nebraska, and Pierce v. Society of Sisters. The Court, however, chose to rely explicitly only on Buchanan because the other cases were too closely associated with Lochner.

Another surprise is that the proposition that Bolling has

come to stand for, that the Fifth Amendment prohibits discrimination by

the Federal Government, was not simply made up by the Supreme Court,

but has a basis in longstanding precedent.

Finally, Bolling is an important example of the distorting effect of Lochnerphobia on Supreme Court jurisprudence. Bolling would have been a much stronger opinion had it been willing to explicitly rely on Lochner era precedents such as Meyer, and to employ a more explicitly Lochnerian view of the Due Process Clause.

|

|